One of the pleasures of maintaining the crowdsourced transcription tool list is learning about systems I'd never heard about before. One of these is Unbindery, a tool being built by Ben Crowder for audio and manuscript transcription as well as OCR correction. Ben was gracious enough to grant me an interview, even though he's concentrating on the final stretch of development work on Unbindery.

First, let me wish you luck as you enter the final push on Unbindery.

What would you say is the most essential feature you have left to work

on?

Thanks! Probably private projects -- I've been looking forward to using Unbindery to transcribe my journals, but haven't wanted them to be open for just anyone to work on. I'm also very excited about chunking audio into small segments (I used to publish an online magazine where we primarily published interviews, and transcribing two hours of audio can be really daunting).

Tell us more about how Unbindery handles both audio transcription and

manuscript transcription. Usually those tools are very different,

aren't they?

The audio transcription part started out as Crosswrite, a little proof-of-concept I threw together when I realized one day that JavaScript would let me control the playhead on an audio element, making it really easy to write a software version of a transcription foot pedal. I also wanted to start using Unbindery for family history purposes (transcribing audio interviews with my grandparents, mainly, and divvying up that workload among my siblings).

So, to handle both audio transcription and page image transcription, Unbindery has a modular item type editor system. Each item type has its own set of code (HTML/CSS/JavaScript) that it loads when transcribing an item. For example, page images show an image and a text box, with some JavaScript to place a highlight line when you click on the image, whereas audio items replace the image with Crosswrite's audio element (and the keyboard controls for rewinding and fast forwarding the audio). It would be fairly trivial to add, say, an item type editor that lets the user mark up parts of the transcript with XML tags pulled from a database or web service somewhere. Or an editor for transcribing video. It's pretty flexible.

How did you come up with the idea for Unbindery?

I had done some Project Gutenberg work back in 2002, and somewhere along the way I came across Distributed Proofreaders, which basically does the same thing. A few years later, I'd recently gotten home from an LDS mission to Thailand and wanted to start a Thai branch of Project Gutenberg with one of my mission friends. He came up with the name Unbindery and I made some mockups, but nothing happened until 2010 when I launched my Mormon Texts Project. Manually sending batches of images and text for volunteers to proof was laborious at best, so I was motivated to finally write Unbindery. I threw together a prototype in a couple weeks and we've been using it for MTP ever since. I'm also nearing the end of a complete rewrite to make Unbindery more extensible and useful to other people. And because the original code was ugly and nasty and seriously embarrassing.

In my experience, the transcription tools that currently exist are

very much informed by the texts they were built to work with, with

some concentrating on OCR-correction, others on semantic indexing, and

others on mark-up of handwritten changes to the text. How do you feel

like the Mormon Texts Project has shaped the features and focus of

Unbindery?

Mormon Texts Project has been entirely focused on correcting OCR for publication in nice, clean ebook editions, which is why we've gone with a plain old text box and not much more than that. (Especially considering that we were originally posting the books to Project Gutenberg, where our target output format was very plain text.)

What is your grand dream for Unbindery? (Feel free to be sweeping

here and assume grateful, enthusiastic users and legions of cobbler's

elves to help with the code.)

To get men on Mars. No, really, I don't think my dreams for Unbindery are all that grand -- I'd be more than satisfied if it helps make transcription easier for users, whether working alone or in groups, and whether they're publishing ebooks or magazines or transcribing oral histories or journals or what have you.

In an ideal world it would be wonderful if a small, dedicated group of coders were to adopt it and take care of it going forward. But I don't expect that. I'll get it to a state where I can publicly release it and people can use it, but other than bugfixes, I don't see myself doing much active development on Unbindery beyond that point. I know, I know, abandoning my project before it's even out the door makes me a horrible open source developer. But to be honest with you, I don't really even want to be an open source developer -- I'm far more interested in my other projects (like MTP) and I want to get back to doing those things. Unbindery is just a tool I needed, an itch I scratched because there wasn't anything out there that met my needs. People have expressed interest in using it so I'm putting it up on GitHub for free, but I don't see myself doing much with Unbindery after that. Sorry! This is the sad part of the interview.

What programming languages or technical frameworks do you work in?

Unbindery is PHP with JavaScript for the front end. I love JavaScript, but I'm only using PHP because of its ubiquity -- I'd much, much, much rather use Python. But it's a lot easier for people to get PHP apps running on cheap shared hosts, so there you have it.

It seems like you're putting a lot of effort into ease of deployment.

How do you see Unbindery being used? Do you expect to offer hosting,

do you hope people install their own instances, or is there another

model you hope to follow?

I won't be offering hosting, so yes, I'm expecting people to install their own instances, and that's why I want it to be easy to install. (There may be some people who decide to offer hosting for it as well, and that's fine by me.)

How can people get involved with the project?

Coders: The code isn't quite ready for other people to hack on it yet, but it's getting a lot closer to that point. For now, coders can look at my roadmap page to see what tasks need doing. (Also, it won't be long before I start adding issues to GitHub so people can help squash bugs.)

Other people: Once the core functionality is in place, just having people install it and test it would probably be the most helpful.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Jens Brokfeld's Thesis on Crowdsourced Transcription

Although the field of transcription tools has become increasingly popular over the last couple of years, most academic publications on the topic focus on a single project and the lessons that project can teach. While those provide invaluable advice on how to run crowdsourcing projects, they do not lend much help to memory professionals trying to decide which tools to explore when they begin a new project. Jens Brokfeld's thesis for his MLIS degree at Fachhochschule Potsdam is the most systematic, detailed, and thorough review of crowdsourced manuscript transcription tools to date.

After a general review of crowdsourcing cultural heritage, Brokfeld reviews Rose Holley's checklist for crowdsourcing projects and then expands upon the part of my own TCDL presentation which discussed criteria for selecting transcription tools, synthesizing it with published work on the subject. He then defines his own test criteria for transcription tools, about which more below. Then, informed by seventy responses to a bilingual survey of crowdsourced transcription users, Brokfeld evaluates six tools (FromThePage, Refine!, Wikisource, Scripto, T-PEN, and the Bentham Transcription Desk) with forty-two pages (pp. 40-82) devoted to tool-specific descriptions of the capabilities and gaps within each system. This exploration is followed by an eighteen-page comparison of the tools against each other (pp. 83-100). The whole paper is very much worth your time, and can be downloaded at the "Masterarbeit.pdf" link here: "Evaluation von Editionswerkzeugen zur nutzergenerierten Transkription handschriftlicher Quellen".

It would be asking too much of my limited German to translate the extensive tool descriptions, but I think I should acknowledge that I found no errors in Brokfeld's description of my own tool, FromThePage, so I'm confident in his evaluation of the other five systems. However, I feel like I ought to attempt to abstract and translate some of his criteria for evaluation, as well as his insightful analysis of each tool's suitability for a particular target group.

I don't believe that I've seen many of these criteria used before, and would welcome a more complete translation.

His comparison based on target group is even more innovative. Brokfeld recognizes that different transcription projects have different needs, and is the first scholar to define those target groups. Chapter 7 of his thesis defines those groups as follows:

It's very difficult for me to summarize or extract Brokfeld's evaluation of the six different tools for five different target groups, since those comparisons are in tabular form with extensive prose explanations. I encourage you to read the original, but I can provide a totally inadequate summary for the impatient:

After a general review of crowdsourcing cultural heritage, Brokfeld reviews Rose Holley's checklist for crowdsourcing projects and then expands upon the part of my own TCDL presentation which discussed criteria for selecting transcription tools, synthesizing it with published work on the subject. He then defines his own test criteria for transcription tools, about which more below. Then, informed by seventy responses to a bilingual survey of crowdsourced transcription users, Brokfeld evaluates six tools (FromThePage, Refine!, Wikisource, Scripto, T-PEN, and the Bentham Transcription Desk) with forty-two pages (pp. 40-82) devoted to tool-specific descriptions of the capabilities and gaps within each system. This exploration is followed by an eighteen-page comparison of the tools against each other (pp. 83-100). The whole paper is very much worth your time, and can be downloaded at the "Masterarbeit.pdf" link here: "Evaluation von Editionswerkzeugen zur nutzergenerierten Transkription handschriftlicher Quellen".

It would be asking too much of my limited German to translate the extensive tool descriptions, but I think I should acknowledge that I found no errors in Brokfeld's description of my own tool, FromThePage, so I'm confident in his evaluation of the other five systems. However, I feel like I ought to attempt to abstract and translate some of his criteria for evaluation, as well as his insightful analysis of each tool's suitability for a particular target group.

Chapter 5: Prüfkriterien ("Test Critera")

5.1 Accessibility (by which he means access to transcription data from different personal-computer-based clients)

5.1.1 Browser Support

5.2 Findability

5.2.1 Interfaces (including support for such API protocols as OAI-PMH, but including functionality to export transcripts in XML or to import facsimiles)

5.2.2 References to Standards (this includes support for normalization of personal and place names in the resulting editions)

5.3 Longevity

5.3.1 License (is the tool released under an open-source license that addresses digital preservation concerns?)

5.3.2 Encoding Format (TEI or something else?)

5.3.3 Hosting

5.4 Intellectual Integrity (primarily concerned with support for annotations and explicit notation of editorial emendations)

5.4.1 Text Markup

5.5 Usability (similar to "accessibility" in American usage)

5.5.1 Transcription Mode (transcriber workflows)

5.5.2 Presentation Mode (transcription display/navigation)

5.5.3 Editorial Statistics (tracking edits made by individual users)

5.5.4 User Management (how does the tool balance ease-of-use with preventing vandalism?)

I don't believe that I've seen many of these criteria used before, and would welcome a more complete translation.

His comparison based on target group is even more innovative. Brokfeld recognizes that different transcription projects have different needs, and is the first scholar to define those target groups. Chapter 7 of his thesis defines those groups as follows:

Science: The scientific community is characterized by concern over the richness of mark-up as well as a preference for customizability of the tool over simplicity of user interface. [Note: it is entirely possible that I mis-translated Wissenschaft as "science" instead of "scholarship".]

Family History: Usability and a simple transcription interface are paramount for family historians, but privacy concerns over personal data may play an important role in particular projects.

Archives: While archives attend to scholarly standards, their primary concern is for the transcription of extensive inventories of manuscripts -- for which shallow markup may be sufficient. Archives are particularly concerned with support for standards.

Libraries: Libraries pay particular attention to bibliographical standards. They also may organize their online transcription projects by fonds, folders, and boxes.

Museums: In many cases museums possess handwritten sources which refer to their material collections. As a result, their transcriptions need to be linked to the corresponding object.

It's very difficult for me to summarize or extract Brokfeld's evaluation of the six different tools for five different target groups, since those comparisons are in tabular form with extensive prose explanations. I encourage you to read the original, but I can provide a totally inadequate summary for the impatient:

- FromThePage: Best for family history and libraries; worst for science.

- Refine!: Best for libraries, followed by archives; worst for family history.

- Wikisource: Best for libraries, archives and museums; worst for family history.

- Scripto: Best for museums, followed by archives and libraries; worst for family history and science.

- T-PEN: Best for science.

- Bentham Transcription Desk: Best for libraries, archives and museums.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Webwise Reprise on Crowdsourcing

Back in June, the folks at IMLS and Heritage Preservation ran a webinar exploring the issues and tools discussed at the IMLS Webwise Crowdsourcing panel "Sharing Public History Work: Crowdsourcing Data and Sources."

After a introduction by Kevin Cherry and Kristen Laise, Sharon Leon, who chaired the live panel, presented a wonderful overview of crowdsourcing cultural heritage and discussed the kinds of crowdsourcing projects that have been successful -- including, of course, the Papers of the War Department and Scripto, the transcription tool the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media developed from that project. They then ran the video of my own presentation, "Lessons from Small Crowdsourcing Projects", followed by a live demo of FromThePage. Perhaps the best part of the webinar, however, was the Q&A from people all over the country asking for details about how these kinds of projects work.

The recording of the webinar is online, and I encourage you to check it out. (Here's a direct link, if you have trouble.) I'm very grateful to IMLS and Heritage Preservation for their work in making this knowledge accessible so effectively.

After a introduction by Kevin Cherry and Kristen Laise, Sharon Leon, who chaired the live panel, presented a wonderful overview of crowdsourcing cultural heritage and discussed the kinds of crowdsourcing projects that have been successful -- including, of course, the Papers of the War Department and Scripto, the transcription tool the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media developed from that project. They then ran the video of my own presentation, "Lessons from Small Crowdsourcing Projects", followed by a live demo of FromThePage. Perhaps the best part of the webinar, however, was the Q&A from people all over the country asking for details about how these kinds of projects work.

The recording of the webinar is online, and I encourage you to check it out. (Here's a direct link, if you have trouble.) I'm very grateful to IMLS and Heritage Preservation for their work in making this knowledge accessible so effectively.

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Mosman 1914-1918 on FromThePage

The Mosman community in New South Wales is preparing for the centennial of World War One, and as part of this project they've launched mosman1914-1918.net: "Doing our bit, Mosman 1914–1918". The project describes itself as "an innovative online resource to collect and display information about the wartime experiences of local service people," and includes scan-a-thons, hack days, and build-a-thons.

One of their efforts involves transcription of a serviceman's diary with links to related names on local honor boards. I'm delighted to report that they're hosting this project on FromThePage.com, and I look forward to working with and learning from the Mosman team.

Read more about Allan Allsop's diary on the Mosman 1914-1918 project blog and lend a hand transcribing!

One of their efforts involves transcription of a serviceman's diary with links to related names on local honor boards. I'm delighted to report that they're hosting this project on FromThePage.com, and I look forward to working with and learning from the Mosman team.

Read more about Allan Allsop's diary on the Mosman 1914-1918 project blog and lend a hand transcribing!

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

Building a Structured Transcription Tool with FreeUKGen

I'm currently working with FreeUKGen--the

charity behind the genealogy database FreeBMD--to build a general-purpose,

open-source tool for crowdsourced transcription of structured manuscript data into a searchable database.

We're basing our system on the Scribe tool developed for the Citizen Science Alliance for What's the Score at the Bodleian, which originated out of their experience building OldWeather and other citizen science sites.

We are building the following systems:

Although this tool is focused on support for parish registers and census forms, we are intent on creating a general-purpose system for any tabular/structured data. Scribe's data-entry templates are defined in its database, with the possibility to assign different templates to different images or sets of images. As a result, we can use a simple template for a 1750 register of burials or a much more complex template for an 1881 census form. Since each transcribed record is linked to the section of the page image it represents, we have the ability to display the facsimile version of a record alongside its transcript in a list of search results, or to get fancy and pre-populate a transcriber's form with frequently-repeated information like months or birthplaces.

Under the guidance of Ben Laurie, the trustee directing the project, we are committed to open source and open data. We're releasing the source code under an Apache license and planning to build API access to the full set of record data.

We feel that the more the merrier in an open-source project, so we're looking for collaborators, whether they contribute code, funding, or advice. We are especially interested in collaborators from archives, libraries, and the genealogy world.

We're basing our system on the Scribe tool developed for the Citizen Science Alliance for What's the Score at the Bodleian, which originated out of their experience building OldWeather and other citizen science sites.

We are building the following systems:

- A new tool for loading image sets into the Scribe system and attaching them to data-entry templates.

- Modifications to the Scribe system to handle our volunteer organization's workflow, plus some usability enhancements.

- A publicly-accessible search-and-display website to mine the database created through data entry.

- A reporting, monitoring, and coordinating system for our volunteer supervisors.

Although this tool is focused on support for parish registers and census forms, we are intent on creating a general-purpose system for any tabular/structured data. Scribe's data-entry templates are defined in its database, with the possibility to assign different templates to different images or sets of images. As a result, we can use a simple template for a 1750 register of burials or a much more complex template for an 1881 census form. Since each transcribed record is linked to the section of the page image it represents, we have the ability to display the facsimile version of a record alongside its transcript in a list of search results, or to get fancy and pre-populate a transcriber's form with frequently-repeated information like months or birthplaces.

Under the guidance of Ben Laurie, the trustee directing the project, we are committed to open source and open data. We're releasing the source code under an Apache license and planning to build API access to the full set of record data.

We feel that the more the merrier in an open-source project, so we're looking for collaborators, whether they contribute code, funding, or advice. We are especially interested in collaborators from archives, libraries, and the genealogy world.

Labels:

client projects,

indexing,

structured transcription

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

ReportersLab Reviews FromThePage

Tyler Dukes has written a concise introduction to the issues with handwritten material and a lovely review of FromThePage at ReportersLab:

Even when physical documents are converted into digital format, subtle inconsistencies in handwriting prove too much for optical character recognition software. The best computer scientists have been able to do is apply various machine learning techniques, but most of these require a lot of training data — accurate transcriptions deciphered by humans and fed into an algorithm.I don't know much about the world of investigative journalism, but it wouldn't surprise me if it holds as many intriguing parallels and new challenges as I've discovered among natural science collections. Handwriting might still be the most interdisciplinary technology.

“Fundamentally, I don’t think that we’re going to see effective OCR for freeform cursive any time soon,” Brumfield said. “The big successes so far with machine recognition have been in domains in which there’s a really constrained possibilities for what is written down.”

That means entries like numbers. Dates. Zip codes. Get beyond that, and you’re out of luck.

Monday, September 24, 2012

Bilateral Digitization at Digital Frontiers 2012

This is a transcript of the talk I gave at Digital Frontiers 2012.

Abstract: One of the ironies of the Internet age is that traditional standards for accessibility have changed radically. Intelligent members of the public refer to undigitized manuscripts held in a research library as "locked away", even though anyone may study the well-cataloged, well-preserved material in the library's reading room. By the standard of 1992, institutionally-held manuscripts are far more accessible to researchers than uncatalogued materials in private collections -- especially when the term "private collections" includes over-stuffed suburban filing cabinets or unopened boxes inherited from the family archivist. In 2012, the democratization of digitization technology may favor informal collections over institutional ones, privileging online access over quality, completeness, preservation and professionalism.

Will the "cult of the amateur" destroy scholarly and archival standards? Will crowdsourcing unlock a vast, previously invisible archive of material scattered among the public for analysis by scholars? How can we influence the headlong rush to digitize through education and software design? This presentation will discuss the possibilities and challenges of mass digitization for amateurs, traditional scholars, libraries and archives, with a focus on handwritten documents.

My presentation is on bilateral digitzation: digitization done by institutions and by individuals outside of institutions and the wall that's sort of in between institutions and individuals.

In 1823, a young man named Jeremiah White Graves moved to Pittsylvania County, Virginia and started working as a clerk in a country store. Also that year he started recording a diary and journal of his experiences. He maintained this diary for the next fifty-five years, so it covers his experience -- his rise to become a relatively prominent landowner, tobacco farmer, and slaveholder. It covers the Civil War, it covers Reconstruction and the aftermath. (This is an entry covering Lee's surrender.)

In addition to the diary, he kept account books that give you details of plantation life that range from -- that you wouldn't otherwise see in the diaries. So for example, this is his daughter Fanny,

And this is a list of every single article of clothing that she took with her when she went off to a boarding school for a semester.

Perhaps more interesting, this is a memorandum of cash payments that he made to certain of his enslaved laborers for work on their customary holidays -- another sort of interesting factor. I got interested in this because I'm interested in the property that he lived in. The house that he built is now in my family, and I was doing some research on this. Since these account books include details of construction of the house, I spent a lot of time looking for these books. I've been looking for them for about the last ten years. I got in contact with some of the descendants of Jeremiah White Graves and found out through them that one of their ancestors had donated the diaries to the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia. I looked into getting them digitized and tried to get some collaboration [going] with some of the descendants, and one of them in particular, Alan Williams, was extremely helpful to me. But this was his reaction:

Okay. So we have diaries that are put in a library -- I believe one of the top research libraries in the country -- and they are behind a wall. They are locked away from him.

So let's talk about walls. From his perspective, the fact that these diaries--these family manuscripts of his--are in the Alderman Library means:

The prevalent practice in institutions was "scan-and-dump": make some scans, put them in a repository online.

One of the problems with that is that you have very limited metadata. The metadata is usually institutionally-oriented. No transcripts, in particular -- nobody has time for this. And quite often, they're in software platforms that are not crawlable by search engines.

Now meanwhile, amateurs are digitizing things, and they're doing something that's actually even worse! They are producing full transcripts, but they're not attaching them to any facsimiles. They're not including any provenance information or information about where their sources came from. Their editorial decisions about expanding abbreviations or any other sorts of modernizations or things like that -- they're invisible; none of those are documented.

Worst of all, however, is that the way that these things are propagated through the Internet is through cut-and-paste: so quite often from a website to a newsgroup to emails, you can't even find the original person who typed up whatever the source material was.

So how do we get to deep digitization and solve both of these problems?

The challenges to institutions, in my opinion, come down to funding and manpower. As we just mentioned, generally archives don't have a staff of people ready to produce documentary editions and put them online.

Outside institutions, the big challenge is standards; it is expertise. You've got manpower, you've got willingness, but you've got a lot of trouble making things work using the sorts of methodologies that have come out of the scholarly world and have been developed over the last hundred years.

So how do we fix these challenges?

One possible solution for institutions is crowdsourcing. We've talked about this this morning; we don't need to go into detail about what crowdsourcing is, but I'd like to talk a little bit about who participates in crowdsourcing projects and what kinds of things they can do and what this says about [crowdsourcing projects]. I've got three examples here. OldWeather.org is a project from GalaxyZoo, the Zooniverse/Citizen Science Alliance. The Zenas Matthews Diary was something that I collaborated with the Southwestern University Smith Library Special Collections on. And the Harry Ransom Center's Manuscript Fragments Project.

Okay, in Old Weather there are Royal Navy logbooks that record temperature measurements every four hours: the midshipman of the watch would come out on deck and record barometric pressure, wind speed, wind direction and temperature. This is of incredible importance for climate scientists because you cannot point a weather satellite at the south Pacific in 1916. The problem is that it's all handwritten and you need humans to transcribe this.

They launched this project three years ago, I believe, and they're done. They've transcribed all the Royal Navy logs from the period essentially around World War I -- all in triplicate. So blind triple keying every record. And the results are pretty impressive.

Each individual volunteer's transcripts tend to be about 97% accurate. For every thousand logbook entries, three entries are going to be wrong because of volunteer error. But this compares pretty favorably with the ten that are actually honestly illegible, or indeed the three that are the result of the midshipman of the watch confusing north and south.

So in terms of participation, OldWeather has gotten transcribed more than 1.6 million weather observations--again, all triple-keyed--through the efforts of sixteen thousand volunteers who've been transcribing pages from a million pages of logs.

So what this means is that you have a mean contribution of one hundred transcriptions per user. But that statistic is worthless!

Because you don't have individual volunteers transcribing one hundred things apiece. You don't have an even distribution. This is a color map of contributions per user. Each user has a square. The size of the square represents the quantity of records that they transcribed. And what you can see here is that of those 1.6 million records, fully a tenth (in the left-hand column) were transcribed by only ten users.

So we see this in other projects. This is a power-law distribution in which most of the contributions are made by a hand-full of "well-informed enthusiasts". I've talked elsewhere about how this is true in small projects as well. What I'd like to talk about here is some of the implications.

One of the implications is that very small projects can work: This is the Zenas Matthews Diaries that were transcribed on FromThePage by one single volunteer -- one well-informed enthusiast in fourteen days.

Before we had announced the project publicly he found it, transcribed the entire 43-page diary from the Mexican-American War of a Texas volunteer, went back and made two hundred and fifty revisions to those pages, and added two dozen footnotes.

This also has implications for the kinds of tasks you can ask volunteers to do. This is the Harry Ransom Center Manuscript Fragments Project in which the Ransom Center has a number of fragments of medieval manuscripts that were later used in binding for later works, and they're asking people to identify them so that perhaps they can reassemble them.

So here's a posting on Flickr. They're saying, "Please identify this in the comments thread."

And look: we've got people volunteering transcriptions of exactly what this is: identifying, "Hey, this is the Digest of Justinian, oh, and this is where you can go find this."

This is true even for smaller, more difficult fragments. Here we have one user going through and identifying just the left hand fragment of this chunk of manuscript that was used for binding.

So crowdsourcing and deep digitization has a virtuous cycle in my opinion. You go through and you try to engage volunteers to come do this kind of work. That generates deep digitization which means that these resources are findable. And because they're findable, you can find more volunteers.

I've had this happen recently with a personal project, transcribing my great-great grandmother's diary. The current top volunteer on this is a man named Nat Wooding. He's a retired data analyst from Halifax County, Virginia. He's transcribed a hundred pages and indexed them in six months. He has no relationship whatsoever to the diarist.

But his great uncle was the postman who's mentioned in the diaries, and once we had a few pages worth of transcripts done, he went online and did a vanity search for "Nat Wooding", found the postman--also named Nat Wooding--discovered that that was his great uncle and has become a volunteer.

Here's the example: this is just a scan/facsimile. Google can't read this.

Google can read this, and find Nat Wooding.

Now I'd like to turn to non-institutional digitization. I said "bilateral" -- this means, what happens when the public initiates digitization efforts. What are the challenges--I mentioned standards--how can we fix those. And why is this important?

Well, there is this--what I call the Invisible Archive, of privately held materials throughout the country and indeed the world. And most of it is not held by private collectors that are wealthy, like private art collectors. They are someone's great aunt who has things stashed away in filing cabinets in her basement. Or worse, they are the heirs of that great aunt, who aren't interested and have them stuck in boxes in their attic. We have primary sources here of non-notable subjects, that are very hard to study because you can't get at them.

But this is a problem that has been solved, outside of manuscripts. It's been solved with photographs. It's been solved by Flickr. Nowadays, if you want to find photographs of African-American girls from the 1960s on tricycles, you can find them on Flickr. Twenty years ago, this was something that was irretrievable. So Flickr is a good example, and I'd like to use it to describe how we might be able to apply it to other fields.

So, in terms of solving the standards problem, amateur digitization has a bad, bad reputation, as you can see here.

And much of that bad reputation is deserved, and isn't specific to digitization. This has been a problem with print editions in the past, it is a problem online now. Frankly, scholars don't trust the materials because they're not up to standard.

How do we solve this? Collaboration: we'd like to see more participation from people who are scholars, who are trained archivists, who are trained librarians to participate in some of these projects.

One of the ones I'm working with [is] digitizing these registers from the Reformation up to the present. We're building this generalizable, open-source, crowdsourced transcription tool and indexing tool for structured data. We'd love to find archivists to tell us what to do, what not to do, and to collaborate with us on this.

Another solution is community. You don't go on Flickr just to share your photos; you go on Flickr to learn to become a better photographer. And I think that creating platforms and creating communities that can come up with these standards and enforce them among themselves can really help.

The same thing is true with software platforms, if they actually prompt users and say: "when you're uploading this image, tell us about the provenance." "Maybe you might want to scan the frontispieces." "Maybe you'd like to tell us the history of ownership."

Those are the things that I think might get us there. I've just hit my time limit, I think, so thanks a lot!

Ben Brumfield is a family historian and independent software engineer. For the last seven years he has been developing FromThePage, an open source manuscript transcription tool in use by libraries, museums, and family historians. He is currently working with FreeUKGen to create an open source system for indexing images and transcribing structured, hand-written material. Contact Ben at benwbrum@gmail.com.

Abstract: One of the ironies of the Internet age is that traditional standards for accessibility have changed radically. Intelligent members of the public refer to undigitized manuscripts held in a research library as "locked away", even though anyone may study the well-cataloged, well-preserved material in the library's reading room. By the standard of 1992, institutionally-held manuscripts are far more accessible to researchers than uncatalogued materials in private collections -- especially when the term "private collections" includes over-stuffed suburban filing cabinets or unopened boxes inherited from the family archivist. In 2012, the democratization of digitization technology may favor informal collections over institutional ones, privileging online access over quality, completeness, preservation and professionalism.

Will the "cult of the amateur" destroy scholarly and archival standards? Will crowdsourcing unlock a vast, previously invisible archive of material scattered among the public for analysis by scholars? How can we influence the headlong rush to digitize through education and software design? This presentation will discuss the possibilities and challenges of mass digitization for amateurs, traditional scholars, libraries and archives, with a focus on handwritten documents.

My presentation is on bilateral digitzation: digitization done by institutions and by individuals outside of institutions and the wall that's sort of in between institutions and individuals.

In 1823, a young man named Jeremiah White Graves moved to Pittsylvania County, Virginia and started working as a clerk in a country store. Also that year he started recording a diary and journal of his experiences. He maintained this diary for the next fifty-five years, so it covers his experience -- his rise to become a relatively prominent landowner, tobacco farmer, and slaveholder. It covers the Civil War, it covers Reconstruction and the aftermath. (This is an entry covering Lee's surrender.)

In addition to the diary, he kept account books that give you details of plantation life that range from -- that you wouldn't otherwise see in the diaries. So for example, this is his daughter Fanny,

And this is a list of every single article of clothing that she took with her when she went off to a boarding school for a semester.

Perhaps more interesting, this is a memorandum of cash payments that he made to certain of his enslaved laborers for work on their customary holidays -- another sort of interesting factor. I got interested in this because I'm interested in the property that he lived in. The house that he built is now in my family, and I was doing some research on this. Since these account books include details of construction of the house, I spent a lot of time looking for these books. I've been looking for them for about the last ten years. I got in contact with some of the descendants of Jeremiah White Graves and found out through them that one of their ancestors had donated the diaries to the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia. I looked into getting them digitized and tried to get some collaboration [going] with some of the descendants, and one of them in particular, Alan Williams, was extremely helpful to me. But this was his reaction:

Okay. So we have diaries that are put in a library -- I believe one of the top research libraries in the country -- and they are behind a wall. They are locked away from him.

So let's talk about walls. From his perspective, the fact that these diaries--these family manuscripts of his--are in the Alderman Library means:

- They're professionally conserved -- great!

- They're publicly accessible, so anyone can walk in and look at them in the Reading Room.

- They're cataloged, which would not be the case if they'd still been sitting in his family.

- On the down side, they're a thousand miles away: they're in Virginia, he's in Florida, I'm in Texas. We all want to look at these, but it's awfully hard for people to get there if we don't have research budgets.

- We have to deal with reading room restrictions if we actually get there.

- Once we work on getting things digitized we have these permission-to-publish that we need to deal with, which have some moral challenges for someone from whose family these diaries came from.

- And we have the scanning fees: the cost of getting them scanned by the excellent digitization department at the Alderman Library is a thousand dollars. Which is not unreasonable, but it's still pretty costly.

The prevalent practice in institutions was "scan-and-dump": make some scans, put them in a repository online.

One of the problems with that is that you have very limited metadata. The metadata is usually institutionally-oriented. No transcripts, in particular -- nobody has time for this. And quite often, they're in software platforms that are not crawlable by search engines.

Now meanwhile, amateurs are digitizing things, and they're doing something that's actually even worse! They are producing full transcripts, but they're not attaching them to any facsimiles. They're not including any provenance information or information about where their sources came from. Their editorial decisions about expanding abbreviations or any other sorts of modernizations or things like that -- they're invisible; none of those are documented.

Worst of all, however, is that the way that these things are propagated through the Internet is through cut-and-paste: so quite often from a website to a newsgroup to emails, you can't even find the original person who typed up whatever the source material was.

So how do we get to deep digitization and solve both of these problems?

The challenges to institutions, in my opinion, come down to funding and manpower. As we just mentioned, generally archives don't have a staff of people ready to produce documentary editions and put them online.

Outside institutions, the big challenge is standards; it is expertise. You've got manpower, you've got willingness, but you've got a lot of trouble making things work using the sorts of methodologies that have come out of the scholarly world and have been developed over the last hundred years.

So how do we fix these challenges?

One possible solution for institutions is crowdsourcing. We've talked about this this morning; we don't need to go into detail about what crowdsourcing is, but I'd like to talk a little bit about who participates in crowdsourcing projects and what kinds of things they can do and what this says about [crowdsourcing projects]. I've got three examples here. OldWeather.org is a project from GalaxyZoo, the Zooniverse/Citizen Science Alliance. The Zenas Matthews Diary was something that I collaborated with the Southwestern University Smith Library Special Collections on. And the Harry Ransom Center's Manuscript Fragments Project.

Okay, in Old Weather there are Royal Navy logbooks that record temperature measurements every four hours: the midshipman of the watch would come out on deck and record barometric pressure, wind speed, wind direction and temperature. This is of incredible importance for climate scientists because you cannot point a weather satellite at the south Pacific in 1916. The problem is that it's all handwritten and you need humans to transcribe this.

They launched this project three years ago, I believe, and they're done. They've transcribed all the Royal Navy logs from the period essentially around World War I -- all in triplicate. So blind triple keying every record. And the results are pretty impressive.

Each individual volunteer's transcripts tend to be about 97% accurate. For every thousand logbook entries, three entries are going to be wrong because of volunteer error. But this compares pretty favorably with the ten that are actually honestly illegible, or indeed the three that are the result of the midshipman of the watch confusing north and south.

So in terms of participation, OldWeather has gotten transcribed more than 1.6 million weather observations--again, all triple-keyed--through the efforts of sixteen thousand volunteers who've been transcribing pages from a million pages of logs.

So what this means is that you have a mean contribution of one hundred transcriptions per user. But that statistic is worthless!

Because you don't have individual volunteers transcribing one hundred things apiece. You don't have an even distribution. This is a color map of contributions per user. Each user has a square. The size of the square represents the quantity of records that they transcribed. And what you can see here is that of those 1.6 million records, fully a tenth (in the left-hand column) were transcribed by only ten users.

So we see this in other projects. This is a power-law distribution in which most of the contributions are made by a hand-full of "well-informed enthusiasts". I've talked elsewhere about how this is true in small projects as well. What I'd like to talk about here is some of the implications.

One of the implications is that very small projects can work: This is the Zenas Matthews Diaries that were transcribed on FromThePage by one single volunteer -- one well-informed enthusiast in fourteen days.

Before we had announced the project publicly he found it, transcribed the entire 43-page diary from the Mexican-American War of a Texas volunteer, went back and made two hundred and fifty revisions to those pages, and added two dozen footnotes.

This also has implications for the kinds of tasks you can ask volunteers to do. This is the Harry Ransom Center Manuscript Fragments Project in which the Ransom Center has a number of fragments of medieval manuscripts that were later used in binding for later works, and they're asking people to identify them so that perhaps they can reassemble them.

So here's a posting on Flickr. They're saying, "Please identify this in the comments thread."

And look: we've got people volunteering transcriptions of exactly what this is: identifying, "Hey, this is the Digest of Justinian, oh, and this is where you can go find this."

This is true even for smaller, more difficult fragments. Here we have one user going through and identifying just the left hand fragment of this chunk of manuscript that was used for binding.

So crowdsourcing and deep digitization has a virtuous cycle in my opinion. You go through and you try to engage volunteers to come do this kind of work. That generates deep digitization which means that these resources are findable. And because they're findable, you can find more volunteers.

I've had this happen recently with a personal project, transcribing my great-great grandmother's diary. The current top volunteer on this is a man named Nat Wooding. He's a retired data analyst from Halifax County, Virginia. He's transcribed a hundred pages and indexed them in six months. He has no relationship whatsoever to the diarist.

But his great uncle was the postman who's mentioned in the diaries, and once we had a few pages worth of transcripts done, he went online and did a vanity search for "Nat Wooding", found the postman--also named Nat Wooding--discovered that that was his great uncle and has become a volunteer.

Here's the example: this is just a scan/facsimile. Google can't read this.

Google can read this, and find Nat Wooding.

Now I'd like to turn to non-institutional digitization. I said "bilateral" -- this means, what happens when the public initiates digitization efforts. What are the challenges--I mentioned standards--how can we fix those. And why is this important?

Well, there is this--what I call the Invisible Archive, of privately held materials throughout the country and indeed the world. And most of it is not held by private collectors that are wealthy, like private art collectors. They are someone's great aunt who has things stashed away in filing cabinets in her basement. Or worse, they are the heirs of that great aunt, who aren't interested and have them stuck in boxes in their attic. We have primary sources here of non-notable subjects, that are very hard to study because you can't get at them.

But this is a problem that has been solved, outside of manuscripts. It's been solved with photographs. It's been solved by Flickr. Nowadays, if you want to find photographs of African-American girls from the 1960s on tricycles, you can find them on Flickr. Twenty years ago, this was something that was irretrievable. So Flickr is a good example, and I'd like to use it to describe how we might be able to apply it to other fields.

So, in terms of solving the standards problem, amateur digitization has a bad, bad reputation, as you can see here.

And much of that bad reputation is deserved, and isn't specific to digitization. This has been a problem with print editions in the past, it is a problem online now. Frankly, scholars don't trust the materials because they're not up to standard.

How do we solve this? Collaboration: we'd like to see more participation from people who are scholars, who are trained archivists, who are trained librarians to participate in some of these projects.

One of the ones I'm working with [is] digitizing these registers from the Reformation up to the present. We're building this generalizable, open-source, crowdsourced transcription tool and indexing tool for structured data. We'd love to find archivists to tell us what to do, what not to do, and to collaborate with us on this.

Another solution is community. You don't go on Flickr just to share your photos; you go on Flickr to learn to become a better photographer. And I think that creating platforms and creating communities that can come up with these standards and enforce them among themselves can really help.

The same thing is true with software platforms, if they actually prompt users and say: "when you're uploading this image, tell us about the provenance." "Maybe you might want to scan the frontispieces." "Maybe you'd like to tell us the history of ownership."

Those are the things that I think might get us there. I've just hit my time limit, I think, so thanks a lot!

Ben Brumfield is a family historian and independent software engineer. For the last seven years he has been developing FromThePage, an open source manuscript transcription tool in use by libraries, museums, and family historians. He is currently working with FreeUKGen to create an open source system for indexing images and transcribing structured, hand-written material. Contact Ben at benwbrum@gmail.com.

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

RMagick Lightning Talk at Austin On Rails

This is a transcript of my five-minute lightning talk at the July meeting of Austin On Rails, the local Ruby on Rails user group. It highlights a few things I've learned from my work on MyopicVicar and Autosplit.

Hi everyone, I'm Ben Brumfield and I've been a professional Ruby on Rails developer for three whole months, [applause] and I am here to talk about RMagick! RMagick is a wrapper for ImageMagick, which is great for processing images. These are the kinds of images that I process:

(I write software that helps people transcribe old handwriting.)

Now is this a pretty image? I don't know. We need to do some things with this, and this is how RMagick has helped me solve some of my problems. One of the things we need to do is to turn it into a thumbnail.

This is an example of RMagic used as a very simple wrapper for ImageMagick: All we're doing is creating an ImageList out of that file, we say image.thumbnail and pass it a scaling factor, and that will very quickly go through and transform that image. Write it to a file and we're done.

So that's kind of basic. RMagick does a lot of other basic kinds of things like this, like rotate or negate--sometimes I get files that are negatives--things like that.

What about the cool stuff? Here's an example of something that I have to deal with.

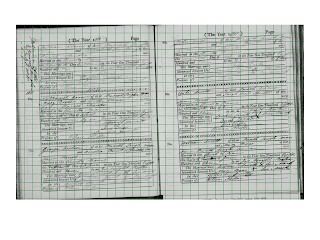

This is a parish registry from 1810, which would be fine, but this is a scan of a bad microfilm of a parish registry from 1810 that is tilted. Now my users need to draw rectangles around individual lines, and the tilt is going to really throw them off.

How badly is this tilted? If you're interested in seeing some RMagick code, here's a script that I wrote to draw a grid over that image or any other image: http://tinyurl.com/GridifyGist . And what you'll see is:

Man, it kind of sucks! You draw a rectangle over that and you're going to get all kinds of weird stuff.

Enter deskew. So here's an example of ruby code, very simple:

Now this looks kind of weird. The image looks off. But the image's contents are not off. And if we throw the grid on it:

You can see that what RMagick has done is that it's gone through and it's looked for lines inside the content of the image, and it's rotated the image in correspondence to where it thinks the lines go and where it thinks the orientation is.

I think that's pretty slick.

RMagick can do some other slick things, and this is where you get into the programming aspects of RMagick and why you'd use RMagick instead of just calling ImageMagick from the command line.

Here what we're doing is extracting files from a PDF. Lots of scanners produce images in PDF format, that is just using PDF as a container for a bunch of images.

This goes through, creates an ImageList from the file, and then goes through for each image in the image list--actually more specifically for each page in that PDF--and it writes it out correctly. (RMagick may not be the right thing to user for some files because it's going to get page by page images -- if you have PDFs that are composed of a bunch of images [on each page] then you're going to want to use some other tools.)

Okay. So here's a file that I'm dealing with, and when I want to present it to my users I actually want to present them with a single page. Is this file a single page? No -- this file is two pages, all scanned on a flatbed scanner. (For those that are curious, it's a sixteenth-century Spanish legal document; I don't know what it says.) But how do I find the spine? How do I know where to split it? It's easy enough to go through and do cropping, but you know, what do we do?

So I came up with this idea: Let's look for vertical dark stripes. Let's look for the darkest strip that is vertical in a deskewed version of this image and see if we can identify that. So this is something we can do. What I've done here is I've said-- this is the inside of a loop where I've said for each x let's pull all the pixels out, and then come up with a total brightness for that image [stripe]. Then later on, I'm going to find the minimum brightness for those vertical stripes.

If I do this on some of the files and indicate that stripe by a red line--which I hope you can see--it did pretty well on this!

It does well on this awful scan of a microfilm, although the red line is hard to see at this resolution.

And wow, it does great on this piece!

This is just an example of using RMagick to solve my problems. After I've gotten the line I want to crop it, so left page/right page

The only caveats that I'd give you about RMagick is that I find it necessary to call GC.start a lot -- at least I did in Ruby 1 6 [ed: 1.8.6] -- because RMagic--I don't know, man--because it swaps out the garbage collector or something and you run out of memory really fast.

RMagick: I love it!

Hi everyone, I'm Ben Brumfield and I've been a professional Ruby on Rails developer for three whole months, [applause] and I am here to talk about RMagick! RMagick is a wrapper for ImageMagick, which is great for processing images. These are the kinds of images that I process:

(I write software that helps people transcribe old handwriting.)

Now is this a pretty image? I don't know. We need to do some things with this, and this is how RMagick has helped me solve some of my problems. One of the things we need to do is to turn it into a thumbnail.

This is an example of RMagic used as a very simple wrapper for ImageMagick: All we're doing is creating an ImageList out of that file, we say image.thumbnail and pass it a scaling factor, and that will very quickly go through and transform that image. Write it to a file and we're done.

So that's kind of basic. RMagick does a lot of other basic kinds of things like this, like rotate or negate--sometimes I get files that are negatives--things like that.

What about the cool stuff? Here's an example of something that I have to deal with.

This is a parish registry from 1810, which would be fine, but this is a scan of a bad microfilm of a parish registry from 1810 that is tilted. Now my users need to draw rectangles around individual lines, and the tilt is going to really throw them off.

How badly is this tilted? If you're interested in seeing some RMagick code, here's a script that I wrote to draw a grid over that image or any other image: http://tinyurl.com/GridifyGist . And what you'll see is:

Man, it kind of sucks! You draw a rectangle over that and you're going to get all kinds of weird stuff.

Enter deskew. So here's an example of ruby code, very simple:

require 'RMagick' # Which is very idiosyncratically capital-R capital-M

s = Magick::ImageList.new('skew.jpg') # We get a new ImageList from skew.jpg

d = s.deskew # And poof! Zap!

d.write('deskew.jpg') # We write out deskew and get this:

Now this looks kind of weird. The image looks off. But the image's contents are not off. And if we throw the grid on it:

You can see that what RMagick has done is that it's gone through and it's looked for lines inside the content of the image, and it's rotated the image in correspondence to where it thinks the lines go and where it thinks the orientation is.

I think that's pretty slick.

RMagick can do some other slick things, and this is where you get into the programming aspects of RMagick and why you'd use RMagick instead of just calling ImageMagick from the command line.

Here what we're doing is extracting files from a PDF. Lots of scanners produce images in PDF format, that is just using PDF as a container for a bunch of images.

This goes through, creates an ImageList from the file, and then goes through for each image in the image list--actually more specifically for each page in that PDF--and it writes it out correctly. (RMagick may not be the right thing to user for some files because it's going to get page by page images -- if you have PDFs that are composed of a bunch of images [on each page] then you're going to want to use some other tools.)

Okay. So here's a file that I'm dealing with, and when I want to present it to my users I actually want to present them with a single page. Is this file a single page? No -- this file is two pages, all scanned on a flatbed scanner. (For those that are curious, it's a sixteenth-century Spanish legal document; I don't know what it says.) But how do I find the spine? How do I know where to split it? It's easy enough to go through and do cropping, but you know, what do we do?

So I came up with this idea: Let's look for vertical dark stripes. Let's look for the darkest strip that is vertical in a deskewed version of this image and see if we can identify that. So this is something we can do. What I've done here is I've said-- this is the inside of a loop where I've said for each x let's pull all the pixels out, and then come up with a total brightness for that image [stripe]. Then later on, I'm going to find the minimum brightness for those vertical stripes.

If I do this on some of the files and indicate that stripe by a red line--which I hope you can see--it did pretty well on this!

It does well on this awful scan of a microfilm, although the red line is hard to see at this resolution.

And wow, it does great on this piece!

This is just an example of using RMagick to solve my problems. After I've gotten the line I want to crop it, so left page/right page

The only caveats that I'd give you about RMagick is that I find it necessary to call GC.start a lot -- at least I did in Ruby 1 6 [ed: 1.8.6] -- because RMagic--I don't know, man--because it swaps out the garbage collector or something and you run out of memory really fast.

RMagick: I love it!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)